Cervical cancer screening has dramatically reduced new cases and deaths from the disease over the past 50 years. But the percentage of women in the United States who are overdue for cervical cancer screening has been growing, and the reasons have not been clear.

To better understand the decline in cervical screening, researchers analyzed data on more than 20,000 women who were eligible for screening in the United States. Between 2005 and 2019, the analysis showed, the rates of timely cervical cancer screening fell overall.

In addition, the analysis showed disparities among groups of women. In 2019, compared with non-Hispanic White women, Asian and Hispanic women were more likely to be overdue for screening, as were women who lived in rural areas, lacked insurance, or identified as lesbian, gay, bisexual, queer, other, or unsure (LGBQ+).

The most common reason study participants gave for not receiving timely screening was lack of knowledge about screening or not knowing they needed screening, according to findings published in JAMA Network Open on January 18.

“Cervical cancer is preventable,” said lead investigator Ryan Suk, PhD, of the University of Texas Health Science Center in Houston. “But the incidence of the disease is higher than it should be, and there are large disparities in the rates of timely screening among women of different sociodemographic groups.”

The new findings highlight how important it is for health care providers to recommend cervical cancer screenings to their patients, Suk continued. Awareness campaigns that use culturally appropriate messages are needed to promote cervical screening to groups with lower-than-optimal screening rates, she added.

In addition, the role of clinicians in contributing to improvements in cervical screening rates deserves further study, according to the study authors.

“The increase in the proportion of women who said they did not know screening was needed or that they did not have a recommendation from a health care provider is surprising and concerning,” said Veronica Chollette, RN, of NCI’s Health Systems and Interventions Research Branch, who was not involved in the research.

The marked decline in up-to-date screening for cervical cancer over time occurred even as new legislation was expanding access to effective screening tests. For example, the expansion of Medicaid in many states and certain provisions of the Affordable Care Act have increased coverage of recommended screenings.

As access to care continues to improve, Suk said, recommendations from health professionals for their patients to get screened will likely become increasingly important for improving screening rates.

Defining up-to-date screening for cervical cancer

Nearly all cases of cervical cancer are caused by persistent infection with high-risk types of human papillomavirus (HPV). For decades, screening with the Pap test (cytology) has allowed doctors to detect precancerous changes that could lead to cancer or the disease in its early stages, when it is most treatable. More recently, HPV testing and HPV/Pap cotesting have become available for cervical cancer screening.

While previous studies have reported declines in up-to-date screening for cervical cancer, Dr. Suk and her colleagues wanted to assess patterns of cervical screening in the United States by sociodemographic groups and try to learn why many women were overdue for screening.

To do so, they used data from the National Health Interview Survey for 2005 and 2019. Participants in the survey answered questions about various demographic, health behavior, and health care characteristics in a structured face-to-face interview.

The researchers defined being up to date on screening based on the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommendations that were in effect in 2005 and 2019. In 2005, that meant screening women aged 21 to 65 with a Pap test every 3 years.

Over time, the USPSTF recommendations evolved. In 2019 (and in 2022), up-to-date screening was defined as screening women aged 21 to 29 every 3 years with a Pap test alone and for women aged 30 to 65 screening every 3 years with a Pap test alone or every 5 years with HPV testing or HPV/Pap cotesting.

Changes to the guidelines during the study period may have caused confusion among patients and doctors about the timing and recommended intervals for screening, according to the researchers.

Results on cervical screening from the National Health Interview Survey

Using the National Health Interview Survey data, the researchers found that the percentage of women overall who were not up to date on screening jumped from 14% in 2005 to 23% in 2019.

Courtesy of National Cancer Institute

When the findings were analyzed by race and ethnicity, Asian women were most likely to be overdue for screening in 2019 (31%). Although the reasons for that aren’t clear, the incidence of cervical cancer among Asian women is not as high as in other groups, so these women might not think they’re at high risk, Suk noted.

“Nonetheless,” she continued, “Asian women still need to be screened for this potentially deadly cancer.”

Rates of overdue screening were also higher among women who identified as LGBQ+ than among heterosexual women in 2019 (32% versus 22%). The National Health Interview Survey offers only two gender categories, male or female, so the researchers could not identify transgender individuals.

“The inclusion of women identifying as LGBQ+ in the study is particularly important,” said Chollette. “The number of individuals identifying as LGBQ+ is rising, and reasons for their low cervical cancer screening rates are poorly understood and largely unexplored.”

Possible reasons for not being up to date on cervical screening

The researchers also investigated potential reasons for the decrease in timely screening rates over time. Among the women who were not up to date on screening, 60% of women aged 21 to 29 years and 55% of women aged 30 to 65 years said “not knowing they needed screening” was the reason for being overdue for screening.

“Not knowing they needed screening” was the most common reason for being overdue across all groups, ranging from 47.2% of women identifying as LGBQ+ to 64.4% of women with Hispanic ethnicity.

Just 1% of women aged 21 to 29 reported that receiving the HPV vaccine was the main reason for not being up to date on screening. People who have been vaccinated against HPV still should be screened for cervical cancer because current vaccines do not protect against all HPV types that cause cervical cancer.

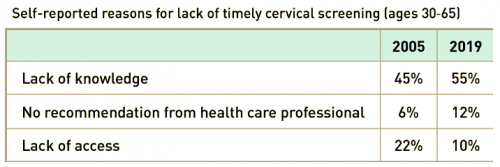

Over time, lack of access declined as a reason for being overdue for cervical screening, the researchers noted. From 2005 to 2019, the proportion of women aged 30 to 65 years who reported lack of access as a primary reason for not receiving screening decreased from 22% to 10%.

During this period in this population, however, lack of knowledge about screening as the primary reason increased (from 45% to 55%), as did not receiving recommendations from health care professionals (from 6% to 12%).

The fact that “not knowing that screening was needed” increased over time as a reason for not being up to date on screening across most sociodemographic groups underscores the need to develop strategies to increase screening awareness for all women, according to the study authors.

Courtesy of National Cancer Institute

Improving cervical cancer screening rates among diverse populations

A limitation of the study was that participants could select only one response as the primary reason for not being up to date on cervical screening, the study authors acknowledged. Many women, including those who lack insurance, those from racial and ethnic minority groups, and those who identify as LGBQ+, may experience multiple barriers to screening, they noted.

The authors also cautioned that reducing the burden of cervical cancer will involve more than just improving timely cervical cancer screening rates. Another challenge is ensuring that women follow up with their health care providers after abnormal findings from cervical screening.

The pandemic has likely worsened the situation documented in the study, Chollette said. Once the pandemic hit, screening for all cancers dropped off as many people delayed or cancelled their scheduled appointments.

Future studies could focus on why current approaches for informing people about cervical screening (e.g., electronic reminders from health care professionals, chart reviews prior to appointments, and posters in waiting rooms) have failed to improve screening rates, Chollette said.

If a primary reason for the decline in cervical cancer screening is due to women not being aware that screening is needed, she added, “then researchers need to explore why providers are not recommending cervical cancer screening.”

Primary care physicians need to keep track of screening schedules for multiple cancers, Suk acknowledged.

“We need more effective and efficient tools and systems that help clinicians stay up to date on screening guidelines,” she continued. “We also need more research on the barriers that prevent clinicians from administering cervical cancer screening.”

This post was originally published by the National Cancer Institute. It is republished with permission.

Comments

Comments