The American Society for Clinical Oncology (ASCO) Gastrointestinal Cancers Symposium took place this week in San Francisco. I haven’t seen an attendance figure, but it was certainly many times smaller than the organization’s massive annual meeting in June.

I appreciate these smaller meetings because it’s easier to chat with researchers and advocates. What’s more, because there’s usually just one session going on at a time, you can focus on the topic without monitoring the Twitter stream from dozens of concurrent sessions.

A pair of themes stood out for me at GI20. First, treating gastrointestinal cancer is hard. We heard a succession of negative studies showing that the regimens being tested failed to work better than the existing standard of care.

But negative studies can teach us something too, such as which approaches to abandon. Commenting on a pair of negative pancreatic cancer trials, Andrea Wang-Gillam, MD, PhD, of the Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis said that such results are reason to buck the trend of skipping from Phase I to Phase III studies. Phase II trials can provide important “no-go” signals that can prevent wasting resources and researchers’ and patients’ time on large studies of futile therapies.

The second theme was a growing emphasis on the patient experience. A number of presentations described patient-reported outcomes and quality of life measures from recent studies that previously reported more typical endpoints. I’ll be writing more about those results soon.

Courtesy of Christopher Booth, MD

Response rates—meaning tumor shrinkage—and progression-free survival are commonly reported as trial outcomes, but what really matters is overall survival and quality of survival, according to Christopher Booth, MD, of Queen’s University. In 2018, Booth coauthored a commentary in the Lancet arguing for cancer “groundshots” to get adequate, affordable care to a broad global population in parallel with high-tech, high-cost “moonshots.”

A few sessions at GI20 were concurrent, which presented a dilemma Friday morning. I opted for a symposium on "Symptom Management—Options in the Era of Legalized Marijuana and the Opioid Crisis."

Kent Hutchison, PhD, Eduardo Bruera, MD, and Donald Abrams, MDLiz Highleyman

Donald Abrams, MD, of the University of California, San Francisco, Osher Center for Integrative Medicine, was among the first to treat and study people living with HIV in the early 1980s. Fighting barriers imposed by its controlled substance status, Abrams studied cannabis to relieve symptoms such as wasting and peripheral neuropathy in people with AIDS; he is now studying it in people with cancer.

Several studies have found that cannabis or its components can help relieve cancer symptoms and side effects of treatment including nausea, loss of appetite, insomnia and pain. As far as its potential as a cancer treatment, Abrams is not convinced due to absent or insufficient evidence. As he wrote in a recent JAMA Oncology viewpoint, preclinical studies have shown that cannabinoids like THC and CBD inhibit the growth of cancer cells in the laboratory; he added that their antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects may also play a role.

But, as he told Forbes, “I’ve been an oncologist in San Francisco for 37 years. If cannabis cured cancer, I would have seen a lot more survivors.”

Courtesy of Kent Hutchison, PhD

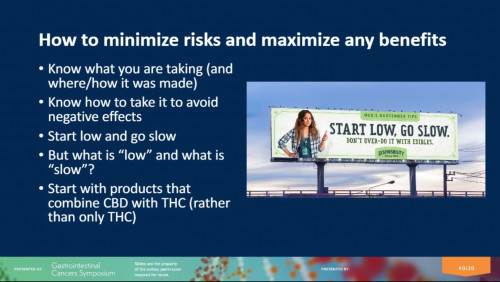

Kent Hutchison, PhD, of the University of Colorado followed with advice for oncologists about advising patients about marijuana as more and more states legalize medical or recreational use. Although 70% of cancer patents in one study wanted information about cannabis from a doctor or nurse, only 40% had received it. Others got their information from friends and family members, newspapers and magazines, websites and social media.

Acknowledging that it’s not currently possible to make empirically supported statements about specific doses, formulations or therapeutic effects, Hutchison suggested approaching cannabis use from a harm reduction perspective. His advice? “Start low and go slow,” meaning start with a low dose and increase gradually as you learn more about how it affects you.

Learn more about preventing hepatocellular carcinoma from UT Southwestern’s @docamitgs, Medical Director of the Liver Tumor Program and Clinical Chief of Hepatology, at the @ASCO #GI20 Gastrointestinal Cancers Symposium. https://t.co/uyhJzTnOsn pic.twitter.com/N8kTvIzZmv

— UTSW Simmons Comprehensive Cancer Center (@utswcancer) January 24, 2020

Opting for the cannabis talks unfortunately meant missing Amit Singal, MD, of the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, speaking on liver cancer surveillance for people with non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH).

Now that hepatitis B can be prevented with a vaccine and hepatitis C can be easily cured with antiviral medications, NASH and its less severe form, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), are a growing cause of liver complications including cirrhosis, hepatocellular carcinoma and liver transplantation. As such, fatty liver disease is a growing focus of our sister publication, Hep. I have Singal’s slides and will be writing more about this soon.

6/11 "Pharma has a tremendous lobby and health policy has remained stagnant around drug pricing. What is a realistic path forward?"

— Yousuf Zafar, MD MHS (@yzafar) January 25, 2020

Campaign finance reform.

Oh wait. You said realistic. #GI20 pic.twitter.com/ywoqQwcuec

Next up, Yousuf Zafar, MD, MHS, of Duke Cancer Institute, gave a great keynote talk on what’s next after precision oncology. Delving into the small proportion of patients who currently benefit from precision oncology and the high cost of cancer care, Zafar argued for precision delivery: ensuring that the right patient receives the right treatment at right time and at the right cost. Asked about how to reign in costs, he suggested that drug price negotiation could play a role, but the most beneficial would be campaign finance reform to curb the influence of lobbyists.

Another highlight for me was Saturday’s keynote by Susan Bullman, PhD, of the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center in Seattle, on how the microbiome impacts cancer, immunity and response to therapy. I wrote a feature on this topic for the Summer 2019 issue of Cancer Health, mostly related to research on melanoma, so it was interesting to hear about the microbiome’s role in colorectal and pancreatic cancers. Read more about Bullman’s work here.

Colontown advocatesLiz Highleyman

Finally, no conference would be complete without advocates. Colontown generously invited me to their cocktail party Friday night for patients, advocates and oncologists. Colontown is an online community of Facebook groups for people living with colorectal cancer, survivors and care partners. Its parent site, Paltown, ultimately aims to create more communities for people with other types of cancer, according to Paltown president Erika Brown.

ColontownCourtesy of Colontown

Comments

Comments